Incredibly enough, it's now nearly ten years since SARS became an international crisis and turned much of China inside out. SARS affected my impressions of China more than any other issue and shaped the tone of this blog for years. Below are my recollections of this turbulent time.

Life and Death in Beijing in the Age of SARS

It was the winter of 2002 and I was having a difficult time in Beijing. I was wondering whether I wanted to live there at all. On my first night in my new apartment I lay down on the bed and it collapsed onto the floor with a crash. As it got colder my central heating only worked about half the time. Sometimes I slept in an overcoat. I had to send part of my salary back to the US to pay for my mortgage and soon learned the bank simply wouldn't let me. The government wanted to keep all the renminbi in China. And I wasn't quite prepared for the culture shock of rampant line-cutting, drivers who saw pedestrians as moving targets, questionable sanitation practices and worse.

I was eventually going to be enthralled with Beijing, but in the winter of 2002 all I felt was frustration, intensified by weather so brutally cold I could barely step outside. Everything was going wrong. Just when I thought things couldn't get any worse, my blog suddenly became inaccessible (along with all other Blogspot blogs; I could get in the back end to post, but I couldn't see the blog.) I had started it several months earlier in Hong Kong and it had become an important part of my life, my one creative outlet. January marked the month that my blog posts became increasingly political. I was fed up with the censorship, the idiotically cheerful spin all stories received in the state-controlled media, the government's obvious prevarications, the blatant propaganda that was always on the television. I let it all out on my blog. And now I couldn't open it.

The day I first read about a strange new disease afflicting southern China there was record cold, and the wind sliced across my face as I walked from my apartment to the subway to work. It was mid-February of 2003. I had just taken off my heavy lambs-wool coat and turned on my PC when the story flashed across my screen: an unidentified disease was infecting people in Guangdong province. It was a respiratory infection and health workers had no idea what it was. More than 200 had been infected and five had died. It was a lead item on Yahoo News and there wasn't much more information except that Chinese government officials were saying very little about it. No surprise there.

Southern China has long had a reputation of being a breadbasket for new diseases, in particular different strains of flu. As news of the infection spread over the weeks to come, some would hypothesize it was caused by people living in close proximity to animals. At Guangzhou's notorious animal markets wild game and dogs and pigs are jammed into cages adjacent to one another. I had seen a news report about these markets and wondered how people could work amid such squalor. The report, on CNN, showed a young boy, maybe nine years old, wearing shorts and flip-flops, squatting in the slime that covered the floor. Who knew what kind of virus might mutate and spread from one animal to another, and finally to the men working the cages or to shoppers? No matter how it started, it appeared that once again the region had spawned an insidious new pathogen.

The story on my screen said the illness had started infecting people in November of 2002, and immediately I felt my blood pressure rise a notch. Nearly four months, and only now were we hearing of a potentially lethal situation. People's lives were at stake and the government had been sitting on its hands. It brought up all my issues with how the Communist party operated, of how China's leaders' obsession with harmony trumped its concerns for its own people. Bad news was automatically repressed. The government always had to look good.

News of the respiratory infection came in dribs and drabs. At first the government tried to kill the story, deleting references to the disease on blogs and message boards. They soon announced it had been completely controlled in Guangdong province and the threat was over. I remember watching an interview on CCTV-9 with a Western couple in Guangzhou. Smiling like jack-o-lanterns, they heaped praise on the government for eradicating the disease altogether and said how happy people in the city were to know the threat was over. I was immediately suspicious.

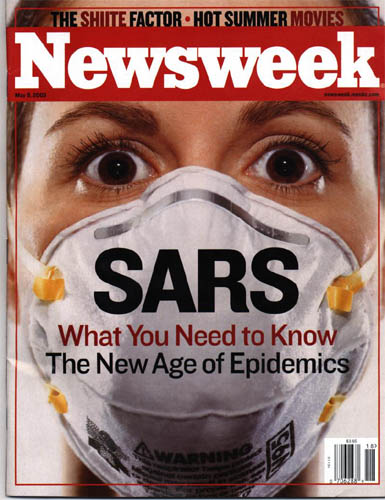

It was only in March that it became apparent Asia had a true crisis on its hands. In the first week of the month the media started reporting that the virus was spreading quickly in Vietnam and Hong Kong. That same week I went on a business trip to Singapore and as I stepped onto the plane I saw for the first time what would soon become commonplace: several passengers were wearing face masks. Seemingly overnight, the mysterious infection became all that people were talking about. The news began to come fast and furious. Every day there were new cases of the untreatable pneumonia-like disease that was soon dubbed Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. "SARS" immediately become a household word.

On March 14th the World Health Organization put out a global alert and an emergency travel advisory for people traveling to and from Asia. That's when I started to really worry. I had planned an April trip that would take me from Guilin to Xian to Yunnan province and then back to Beijing. I decided I was not going to let this disease ruin the trip, and I made all the hotel and flight reservations, something I would come to regret.

In early April, the world went crazy. Schools in Hong Kong were shut down. About half the people on the streets of Beijing were wearing facemasks. Everyone knew people in China were getting sick but the Chinese government was denying there was any threat. On April 11, I noted on my blog (through a VPN), "Needless to say, SARS is a dead story according to Chinese television — only 22 cases in Beijing and all on the road to recovery. As the announcer reads the statistics, I can see she wants to get through the story as quickly as possible. Her face can't hide that she knows she is lying."

Stories were leaking that the government was hiding infected patients from the WHO, driving them around Beijing in ambulances so they couldn't be counted. A prominent Chinese doctor publicly accused the Beijing government of hiding thousands of patients and intentionally deceiving the WHO and, worst of all, its own people. The atmosphere was becoming increasingly surreal.

I was part of an international chorus, mainly expats, that performed every year in Beijing's Forbidden City concert hall. This year we were singing the Faure Requiem, which seemed eerily appropriate. At a rehearsal in early April a chorus member, a professor at Peking University, told me he'd heard that two of his fellow professors had died of SARS and a number of students were infected. Another chorus member, a well-known journalist, said there was a massive cover-up by the government and that hospitals were being strained by the inflow of SARS patients. What was true and what wasn't? By keeping silent, the government had opened the floodgates to rumors of every kind. Rumors were all we had. Within a week Beijing was in chaos.

Word of the cover-up was out and no one knew what to believe. I went to the supermarket to find many of the shelves empty as people stocked up on food and bottled water. Face masks became the rule, not the exception. All movie theaters, Internet bars and schools were closed, as were most restaurants. Nearly all of my clients were foreigners, and every one of them had fled Beijing by mid-April. So I had very little work to do, and began to blog obsessively about SARS.

Everything came to a head on April 20, when the government held an unprecedented live press conference. I watched it in wide-eyed amazement. A government that had insisted Beijing was all but SARS-free was admitting there were more than 3,000 cases. Their cover-up had been exposed and there was no point lying anymore; they really had little choice but to come clean. The officials actually took live questions from foreign journalists, something I never thought I would see in China. The minister of health and the mayor of Beijing were demoted. The government was all but admitting it had been lying about SARS for months. I wrote on my blog, "We are viewing history in the making here in Beijing, all brought about by a nasty variation of the common cold."

Everything was different the next day. Beijing has a vast legion of street sweepers, usually older women brandishing straw brooms. Now I saw them scrubbing down buildings. I went to get money from my ATM, and as if out of nowhere a woman with a bucket was washing the ATM keypad as I walked away. The entire city was being disinfected.

My office was half empty on April 17th and most of my colleagues were wearing masks. Suddenly I heard our receptionist hang up her phone and cry out, "There is SARS in our building!" Everyone jumped up and ran over to her. She had just spoken with the building manager and was told a worker in our tower had died of SARS. I don't think any work was done that day. The next morning when I arrived at the office there was a huge poster on the front window warning that there had been a SARS patient in the building.

I wondered how much more surreal Beijing could become. And I wondered what I was doing here, in a city that had brazenly lied to its people about a deadly infection. I had to fly to Hong Kong to meet with the head of my agency the next day when, on a busy street in Beijing, I received another shock: no taxi would stop for me. They would pull up as normal, but then when they saw my suitcase they all sped away, one after another. Finally a driver was kind enough to pick me up and when we got to the airport the mystery was solved: there were hundreds of taxis parked in rows outside the airport because while people were leaving Beijing in droves, no one was flying in. So they had no passengers to drive back to the city. These drivers were going to sit there for hours.

I started my vacation on April 25, right at the peak of SARS madness. I went with friends to the Mutianyu section of the Great Wall and we were shocked to see only a handful of tourists. Vendors who made their living selling water and soda to tourists surrounded us, begging us to buy something, anything from them. We walked along the wall for two hours, and only passed ten or fifteen visitors along the entire way. Meanwhile, news was coming out that SARS was spreading west and that travel restrictions might be imposed. I was about to head south and then to the west. I didn't know SARS was going to follow me like breadcrumbs.

The first stop was Guilin, and the next surprise was walking into the Sheraton hotel and finding it empty. Tourism in China had essentially shut down. There were only three guests, one of whom was pacing back and forth in the lobby, wearing shorts and a T-shirt. He was incensed that the hotel had turned off all the air conditioning; they decided it would be too expensive to keep the entire building air-conditioned. They were nice enough to put fans in our rooms. I was unhappy, as this was a five-star hotel, but I was also sympathetic; what could they do under the circumstances? The highlight of any trip to the breathtaking city of Guilin is the boat ride up the Li River, alongside of which spires of karst limestone rise sheer from the ground like whales leaping into the sky, enveloping passengers in impossibly beautiful scenery. A friend had joined me, but all the boats were docked; they were forbidden to take passengers. One of China's great tourist attractions was simply shut down. As we walked away from the dock in disappointment, an unlicensed boat operator ran after us and took us on the scenic ride. There was the vast Li River, usually swarming with tour boats, empty except for one small illegal boat chugging up its winding path.

Things were no different in Xian. When we went to see the Terracotta Warriors, there was only a tiny group of visitors, German tourists. We had the warriors all to ourselves. When we left the museum, we were literally accosted by throngs of children selling miniature terracotta warriors. They wouldn't let us pass. They had no customers and they were totally desperate. I asked one boy how much a box of five warriors would cost and he said 10 kuai. I paid him, and another ran up to me and said he would sell me a box for five kuai. A third boy grabbed my legs and tried to stand on my shoes so as not to let go and said he would sell me the same box for one kuai. SARS had decimated China's tourism industry and the misery was spreading down the food chain.

That night I received a frantic call from my travel agent in Beijing: The roads to Yunnan province were being barricaded and no one was permitted to travel from east to west. This was supposed to be the highlight of the trip, with stops at Kunming, Dali, Lijiang and "Shangri-la." What could I do? I thought we could escape from SARS, and now SARS had chased us across the country and won.

I was so frustrated, I felt I had to get out of China for the rest of my vacation and decided to flee to Bangkok. It was already May and the weather there was hot and wet, but I didn't care. Singapore and Hong Kong had strict quarantines for arrivals from China so I couldn't go there. Thailand's screening procedures were relatively lax. As miserable as the heat was, it was still a haven.

Later in May, SARS slowly dissipated and Beijing began its return to normalcy. The foreigners came back and tourism picked up again. I had decided to move out of China, a decision I regret, but at the time I felt I had no choice. SARS was one factor, but certainly not the only one. I couldn't deny, however, that part of me didn't want to leave. Maybe it was the people I came to know, my colleagues whom I loved, the excitement of a country that seemed to vibrate with youth and hope and optimism. I did not at all hate China; I simply had not been ready for it. SARS was the last straw and had driven me over the edge, but there was much more to China than that. Later in Singapore I would write on my blog, "So today, two months since I left Beijing, I carry China in my heart all the time….it is in my dreams, my nightmares, my waking and sleeping."

Everyone knows my attitude toward China evolved dramatically over the next few years, and that I totally fell in love with Beijing after I moved back in 2006. When in 2009 I had to return to the States for family reasons I was devastated and never really got over my homesickness for Beijing. Even now China is like a giant magnet pulling at me. SARS has faded into memory, and I never stop thinking about moving back to China, a country that I never really left. I want to believe SARS provided a valuable lesson to the Chinese government (witness its hyperbolic reaction to swine flu a couple years ago). Being there in the thick of it in 2003, I enjoyed a bird's eye view into how the Chinese government operates. It wasn't pretty, but in retrospect I am glad I was there to experience it. The entire incident, including the censorship and propaganda and the citizens' distrust and the cover-up, provided a microcosm of life in China at the time, one that I will never forget.

Read More » Source